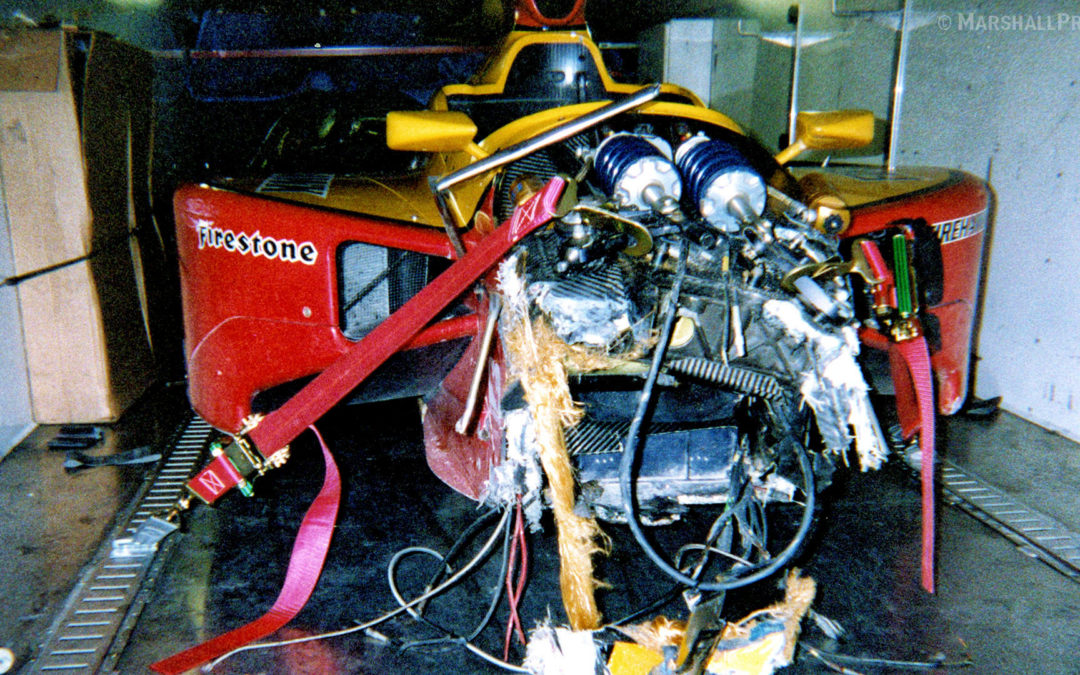

It was the obvious destruction that stood out from across the Texas Motor Speedway garages. As it returned to us on the back of a tow truck, the jarring observation came from what wasn’t there: The front half of our No. 99 Sam Schmidt Motorsports Dallara-Oldsmobile Indy car.

As we got closer to the wreckage, any thoughts of chassis damage gave way to the horrors our driver Davey Hamilton experienced minutes earlier at Turn 2. It was June 9, 2001, and the start of Lap 72 at the Indy Racing League’s Casino Magic 500 permanently changed the Idahoan’s life.

In an era that pre-dated live streaming, mobile phones that doubled as televisions, and an intensive amount of race information that was readily available, the crash happened without anyone on pit lane having much of an idea of what took place. By chance, in my final year working as an IndyCar crew member, I was among the first to know something was wrong; as SSM’s assistant race engineer, I was staring at my laptop and saw Hamilton’s telemetry data go haywire on the screen.

IMS Photo

The spike in some numbers and plummeting of various bars and graphs coincided with a huge roar from the crowd, and together, it was clear we were involved in an accident. The severity of the crash, however, wasn’t visited upon us until the car was delivered to the paddock.

With our race finished, it didn’t take long to break down our pit equipment and walk back to the transporter, and with a request for two volunteers to wait for the car and perform the routine task of wiping it down before loading it into the hauler, I raised my hand, grabbed a bottle of cleaner and a roll of paper towels.

While I don’t recall which teammate joined me in the process, I do know that we started walking over to the other side of the garages where we were told the car would be deposited, and on that short journey, the tow truck arrived faster than expected, backed down the hill, and as we caught a glimpse of the car, there was no need to keep walking once we saw how much blood was on the sidepod. I turned around, went back to the transporter, and traded the paper towels for the larger bath towels we dipped in water and placed over the bodywork covering the hot exhausts when the car was on pit lane during practice sessions.

This cleanup job wasn’t for the squeamish and had nothing to do with clearing bugs and rubber marks away from the car. Although we lacked insights on all that our driver endured in the crash, the large pools of blood inside the cockpit and along the path where he was extricated from the car said Hamilton endured something hellish in Turn 2.

Davey Hamilton. LAT Photographic/F. Peirce Williams

As told by those who lived the experience over the last 20 years, here’s a story of a veteran driver plunged into a nightmare. And a little team, in only its fifth race, trying to deal with disaster, where medical heroes emerged, safety standards were called into question, and life eventually moved on.

Davey Hamilton: It’s crazy how our minds, we remember some things, but then I can’t remember what I had for breakfast. But I remember that whole incident like it happened yesterday. I remember coming up on Jeret Schroeder and just saying, ‘Well, he’s running his line on the bottom, so I’m just gonna go around the outside here.’ And so I went into Turn 1, normal path, and then I seen smoke coming out of his car. The next thing, he just turned on his own oil, got oil on his own tires, which he had no control at that point.

Driving for the Tri Star Motorsports team, Schroeder impressed with a strong run in qualifying to start 15th in the field of 24 with his No. 6 Dallara-Oldsmobile. The New Jersey native was a veteran of the 1990s equivalent of The Road To Indy, and while he wasn’t destined for IndyCar stardom, Schroeder was capable and trustworthy in three Indy 500s and 16 IRL events prior to Texas.

He was dealt an unfair hand with an engine failure, and behind him, a sickening moment in time was about to unfold.

Hamilton: And I just kept on the gas. I wanted to get by him so I kept moving up and I really felt like I cleared him because he’s out of my vision. And then, he barely tapped the back to my car, and man, it was just barely just enough to turn it and then that’s when it all happened.

Schroeder’s pirouetting machine clipped Hamilton, who slid up the track at 200mph-plus, slammed into the concrete wall with the right-front corner of his car, and watched as the No. 99 twisted and started climbing. Hamilton’s Dallara would scale the wall and continue rotating, flying nearly headfirst towards Texas Motor Speedway’s exposed poles erected in front of its fencing system.

Hamilton: After that, I just remember seeing sky and racetrack and then fencing. And I just spun so fast, so many different directions. I knew it was happening. It flew and then it swung the front over the wall and when the front hit one of those poles, that’s what sheared the front of the car off.

Hamilton’s Indy car struck the thick steel pole with the top of the Dallara’s tub, inches in front of where the front dampers were connected to the rocker arms. The immovable steel object and the subsequent interaction with the fence broke the tub away at Hamilton’s knees, and with the contortions taking place, the impact was anything but a clean cut. With the tub’s severing starting at the top, the continuing motion led to the breaking away of the survival cell in a down and rearward trajectory—approximately 45 degrees back—to snap the front of the car away a few inches shy of the dash bulkhead at the bottom of the tub.

Hamilton: Then it swung me back the other way onto the racetrack, but my legs were exposed.

The underside of Hamilton’s legs, from the base of his behind out to his toes, were in clean air. It’s unclear how much damage was received from going into the fencing, but there was no doubt about the next event. With more than 1000 pounds of a car strapped to his back, and while traveling at significant speed, the No. 99 returned to the track nose down and landed feet-first, driving Hamilton’s legs into the ground.

The front of the car was torn away, the gearbox was ripped off the back of the car, and three of the four wheels, along with most of the suspension, was missing. What was left of the car spun down the back straight and came to a rest with Hamilton’s feet and legs mashed into the inside wall.

A stomach-turning photo taken from the inside of Turn 3 depicts the difference between the front of Hamilton’s car and that of Schroeder, in the background, whose Dallara tub is fully intact.

LAT Photographic/F. Peirce Williams

Hamilton: Then it came to a stop, and I knew I hurt. I couldn’t catch my breath. But I had no idea that I was hurt as bad as I was. I felt like I could move. I could move my knees and my legs, but I’m not realizing that they were demolished from the knees down. And I was awake the entire time. I had no other injuries, except for my legs. I was very fortunate to not have head injuries or any internal injuries, but on the downside, man, I felt everything pretty quick.

Today, Arrow McLaren SP co-owner Sam Schmidt is a steady presence on pit lane during NTT IndyCar Series races. But in 2001, little over a year since the devastating crash during testing at Walt Disney World that rendered the IRL race winner a paraplegic, his race-day routine was less defined. For the Casino Magic 500, he was positioned in a hospitality suite overlooking the 1.5-mile oval from atop the grandstands near the start/finish line.

Less than three months into his role as an IndyCar team owner with SSM, which was facilitated by the LP Racing duo of Larry and LeeAnne Nash, Schmidt had a new crisis to handle.

Sam Schmidt: Maybe I should have quit while I was behind. I remember vividly watching that race from the suite because I’d never watched it from that side of the racetrack. And right when the race started, I looked to my wife and said, ‘These guys are nuts. How the hell did you ever let me do this? I mean, can you see how quickly they get from the exit of Turn 2 to Turn 3?’ It’s like, holy shit. This is really fast. And of course, back then, the cars had more downforce, and there was a couple of lanes, racing side by side.

I was watching Davey from a different perspective, and then a guy lost a motor in front of him. He was like a helicopter crashing down the backstretch. You see it all happening in slow motion with the engine blowing and where he was in Turn 1, and you try to scream, but he won’t hear you. It was really bad. I remember just racing out of the suite and get into the infield care center as quick as I could.

LeeAnne Patterson (formerly Nash): Protocol for our group when a driver had a crash was for Larry to deal with the car and for me to go to the infield medical center and coordinate with the family. I made my way to the medical center after collecting Johnny, Davey’s close friend. Mark Wingler, from the IRL Ministries, met me there. Davey’s wife and children were not in attendance, and I believe Mark was on the phone with her.

Hamilton: One thing I can tell you is that God’s good, because you can’t reenact pain, right? You feel it, but you can’t reenact it, thank God. Because I know at the time, it was unbearable. They got me strapped to a backboard to get me out of the car, and my neck’s strapped down. They’re cutting my suit off. And I hear them on the phone saying to the Life Flight (air ambulance) people that it appears to be a double amputee. And I heard that in between my complaining of pain.

And when they were talking on the phone, I thought, honestly, ‘Man, somebody got hurt in that wreck,’ not realizing they’re talking about me. And then I asked the nurse; she was standing trying to comfort me, ‘Are they talking about me?’ And she shook her head, yes. I said, ‘Just check me out. I’m done. I can’t take it no more. I can’t take the pain.’

Patterson: We all heard Davey being brought in. The screams, I will never forget.

Hamilton: And then fortunately, once they found out I had no internal injuries or head injuries, they started giving me the good stuff to knock me out.

Patterson: While I was driving Johnny to the hospital, Sam was already on the phone with Dr. Scheid, and Dr. Scheid was also already in motion, making calls and getting himself to the hospital. Amongst what seemed like commotion, we gathered in a waiting room. People started to assemble post-race. Johnny and Betty Rutherford came.

For Schmidt, arriving at the infield care center at TMS to see Hamilton was like a trip down bad memory lane. Driving for Treadway Racing in 1999, he’d suffered a crash of his own in Texas which, while far less severe than Hamilton’s, left the Las Vegas native with an understanding of how his driver might be handled once he was transferred to a local hospital.

LeeAnne Patterson and Sam Schmidt.

Schmidt: And fortunately or unfortunately, I’d been through the whole process two years earlier. Hit the wall there myself, got loaded in the helicopter, and flown over to Parkland with Scott Goodyear in the same helicopter. Going through the whole process of my feet being twisted, and I don’t know whether you call it ironic or whatever, but when I went to Parkland in 1999, they said it was not repairable.

I lost half of my big toe and maybe a quarter of my second toe, and the original prognosis is they were going to take a lot more than that because in my crash, my feet got all tangled up in the pedals. So I remember Denise Titus and Dr. Kevin Scheid and all those guys from the IRL saying, ‘Let’s get you to Indy so we can fix this.’

And of course, Davey’s was different because it took the front half of the car off, so it was a lot of a lot of severe flesh wounds and bone wounds and from the knees down; it was a mess.

With Hamilton’s feet, ankles, and lower legs pulverized by the repeated impacts, initial optimism was low when it came to saving the crumpled remnants laying on the operating table. Ignoring the obvious destruction sitting in front of them, there was a bigger issue at hand. Not only had Hamilton lost a considerable amount of blood, but after he was admitted and his blood supply was replenished, the doctors learned its life-sustaining flow was not reaching the traumatized areas.

Without blood circulating though his lower legs, the flesh would soon die. Double amputation appeared to be an inevitability.

Patterson: Around 11:45 that night, Dr. Scheid came out and told us that Davey had effectively lost his feet. However, he also said he had found one tiny blood vessel still delivering blood and he knew he could save things.

It’s here where a small glimmer of hope in a dire situation emerged. Of the many things Dr. Scheid achieved in Texas after the crash, refusing to give up—continuing to dig through Hamilton’s mangled legs until blood supplies could be patched in to keep everything alive below the knees—produced a life-changing triumph.

Patterson: The next morning, we went to see Davey, who was all puffed up. The decision to transport was made very quickly.

At Schmidt’s constant urging, and with the help from the IndyCar community to make travel possible, Hamilton would soon be on his way.

Schmidt: And it was kind of the same thing as with me: Don’t let those guys touch Davey, let’s stabilize him, let’s figure out the quickest and medically safest way to get him to Indy so the experts can go to work on him. My wife happened to be there with me and with Davey. It was almost like déjà vu.

Patterson: About three days later he was air lifted back to Indy.

Hamilton: The last thing I remember from Texas is being rolled into the helicopter at the track–I see the helicopter blades—and that’s it until probably a week to 10 days later and I’m in Indy.

Dr. Terry Trammel. IMS Photo.

Dr. Terry Trammel, IndyCar surgeon: I was watching the race, but I wasn’t there. I was home. Those were in the days when we had the two different leagues, and it was Dr. Scheid, my partner, the orthopedic guy for the IRL, and I was on the other side of the fence with CART. But little does anybody know that at this time, we worked on everything together.

Amputation was the current wisdom with most doctors: The only treatment for this is an amputation, so that’s what you do. A lot has changed since then, but the practice said that it’s a waste of time and it’s committing the patient to multiple surgeries and so on to try and save injuries that bad. And that was the prevailing wisdom. They said we would be the first ones to not go in that direction, if you want to be the guys to do it. We said let’s get him back to Indianapolis and put him back together.

Dr. Scheid asked if I was available, and Davey was up here very soon after the crash, because the dressings were still wet and bloody. And we went into surgery, started unwrapping things there. By this point, there was Kevin and I and Dr. Tim Webber. And we’re gonna do both feet at once.

Hamilton: The first surgery was 27 hours.

Trammel: We had it set up so we could have one guy in the middle and a guy on either side, and we’d switch around as was necessary. Started unwrapping things and parts of his legs and feet started falling out. Some of them were hung on by a thread of tissue. We collected up all of this, and the whole initial process was about cleaning everything up and being sure you get all the carbon fiber out. And that’s something that, unfortunately, I had a lot of experience with because you can’t pick out a piece of carbon fiber with a utensil—an operating tool—because it just breaks. And now you have two pieces of carbon fiber get out of out of somebody.

So you either have to wash it out or cut it out and be very, very, very gentle picking it out. Nice, long carbon needles, you can pull out with your fingers, but that’s all. So that’s what we’re doing. We’re cleaning it up. And we ended up with a basket full of parts—bone. And we didn’t have the foresight to separate it into right and left baskets to start with, thinking that we weren’t going to be able to use any of it anyway. And it turned out that when we got everything all cleaned up, we thought well, let’s do some bone grafts put it all back where it came from.

Hamilton: It was a long one, finding and trying to save everything. They told me later they even had one of those skeletons, like you’d have in a classroom; they had one of those in there trying to figure bone stuff out.

Trammel: Think of two jigsaw puzzles that are almost identical. And somebody dumps all the pieces in one box. So literally, we were working where someone on the right would be like, ‘I need the neck of the talus bone, you got one?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, mine’s still inside him, so the one in the basket must be your side.’ And we did that for several hours back and forth and back and forth until we used up all the parts and presumably got them back where they came from and put in some sort of preliminary fixation so they stayed where we put them. And that was round one. All that was to just get the crap out and get the pieces put back in.

Hamilton would go though more surgeries as the repair efforts continued with the IndyCar specialists.

Hamilton: When I finally woke up in Indy, my dad was the first person I saw. And the last thing I remember from Texas is they’re going to amputate my legs. That was the last thing. I didn’t know where I was at, but knew I was in the hospital. And I looked at my dad and said, ‘Did they cut my legs off?’ And he goes, ‘No, you’re in Indy and they’re trying to save them.’ I said, ‘Okay, well, see you in another week. I’m going to check out for a while.’ But when he told me that, that there was a bit of hope. So I just kept a positive attitude to the whole thing as best I could.

Texas aftermath. LAT Photographic. F. Peirce Williams

Although it wasn’t the chosen path for Hamilton, the theme of amputation, and lessons taken from another gruesome feet-first crash in 1984 would steer the process in 2001. It was the great four-time Indy 500 winner Rick Mears, at the Canadian oval in Sanair, where Trammel and Dr. Steve Olvey–Indy car’s traveling surgeons—were thrust into an identical situation that would inform all of their saves going forward.

Trammel: By this point in time with Davey, we had some background in these types of injuries because we had all the stuff that happened to Mears, which was a groundbreaking event.

A very senior orthopedic surgeon in Montreal told Roger Penske that Mears’ feet needed to come off. And Roger looks at Olvey, because I’m up in the operating room, and Roger says, ‘Should we do what he said just said?’ And Olvey says, ‘No, get the plane ready, we’ve got to get to Indianapolis.’ And Roger said ‘Ok.’

I was unaware of all that going on until later. I was in a holding area outside surgery, trying to say we’re not going into surgery, not taking his feet off, because that’s what they wanted to do. They said they were unsalvageable. Anyway, that’s where the saving approach started.

On top of refusing to end Mears’ driving career through amputation, the doctors were steadfast in learning new ways to improve the Californian’s chances of walking and possibly racing again in the future.

Trammel: The person that probably went unheralded that I got a lot of advice from was Dr. Jim Strickland, the hand surgeon here in town, because I remember calling him from outside surgery in the recovery room and saying, ‘Hey, here’s the problem I have, how is a hand different than a foot?’ I said, ‘Can I do whatever I would do to a mangled hand, to a foot?’ And Jim thought for a minute it says ‘Yeah, the only difference is the fingers are shorter.’ And not even that you don’t walk on your hands, because there are a lot of mammals that walk on their hands. And so I just did that first go-round with Mears like what I would have done if it were crushed hands. And I got all that from Strickland.

So that was the beginning. And then along the way, we had others. There was 1992 and that really, really cold Indy 500. We had Nelson Piquet. And I remember with Piquet, one of my partners who was the foot surgeon, came in and really reamed me for not taking his foot off. And I just looked at him and said, ‘That doesn’t happen in this operating room.’

And we have been very fortunate and being able to never have to throw away a whole piece of limb. We lost some parts on Alessandro Zampedri that didn’t survive, but overall, we’ve been able to put things back where they came from and end up with fairly functional feet.

Just recently, I had an opportunity to discuss this with Mears about, ‘Do you wish I’d just taken them off?’ Because he’s lived with pain and aches since then. And he didn’t take a breath before saying absolutely not. Having his feet was way better than not having them.

The Sanair oval, circa 1984.

Hamilton: And another thing is, I was a racing driver, and I had some good things getting ready to happen. Things were going positive up to the crash. On my IndyCar side, I had some opportunities that were coming up with a great team and sponsors and things that we always dreamed of, and that would have gone out the window if they amputated.

And thought, ‘I don’t want to quit racing. I’ve got to get better because I want to race again.’ And I couldn’t really tell anybody that, when you’re lying there, relying on everybody to do everything for you, and you’re in wheelchairs and can’t walk. But every day I’d get up, and that was part of my recovery: I’m going to get better, I’ve got a big incentive to just do everything I could to get better because I wanted to race again.

For Schmidt, other realities would eventually sink in. His primary driver—the IRL’s iron man—was finished for the season, if not for good. His primary chassis was destroyed, a lot of money was lost, and there was a race the following weekend, the Radisson Inn 200 at Pikes Peak International Raceway in Colorado.

A flurry of decisions on whether to continue or regroup, of which driver to hire, and a litany of other questions would only wait so long to be answered.

Schmidt: While Davey was going through that helicopter ride from the track to the hospital, dealing with all that, none of the things as far as the next race or the car, or the economic stuff is on your mind. My first thing was getting to the hospital and figuring out how we are going to run interference. Because there, the doctors are authorized in those hospitals to do anything. And then once you get that covered, as the week goes on, as you can imagine, the phone’s ringing from a lot of people with helmet in hand.

So it’s figuring out the best way to go forward with Davey, but also, you have another car, you have a team, you have people that are relying on you for their livelihood. What would Davey want you to do? Those kinds of things are running through your mind and, for me, my family has always been the kind where you’ve got to persevere. It goes back to my dad getting hurt and I’m picking up the pieces and moving on. And it was the same with me after my last crash.

LP’s Larry Nash would estimate 100 drivers made contact in the days after Hamilton’s crash. One name that always stood out among those Nash cited was Jeff Wood. While decently skilled, the Kansas native was a sporadic IndyCar participant, spreading 50 starts over a 10-year span with some of the smallest and least threatening teams. His last race came in 1994, and although Wood tried to do more, he failed to qualify at the next four races and withdrew from his last attempt in 1995.

Despite being forgotten by time, and with his best finish of 8th coming in his second IndyCar race back in 1983, Wood was among the many who felt compelled to call and lobby for Hamilton’s former seat.

Schmidt would elect to press ahead, and with the second chassis readied—a spare we carried that belonged to Dallara to be used, in case of emergency, by any of the smaller teams who couldn’t afford two cars, SSM paid for the tub, preparations were completed, and we moved northwest from Texas to Colorado.

In need of a break for our minds and spirits, some of us piled into the van and drove up the mountain to enjoy the view from Pikes Peak’s summit.

The author, holding mechanic Paul Taylor with other SSM team members.

CART veteran Richie Hearn was tabbed to drive in Colorado and performed well, finishing ninth while giving SSM a well-deserved boost. Jaques Lazier, the younger and lesser-known brother of 1996 Indy 500 winner Buddy Lazier, was in for the next race as a revolving door of drivers continued throughout the year.

If Pikes Peak’s result was a relief, Lazier moved the bar higher by capturing pole position for us on debut at the Richmond bullring. Although our finishes at Richmond and the next race at Kansas were forgettable, Lazier produced SSM’s best result of the year with a podium—third place—at the ensuing round in Nashville.

But even with that mini victory, adversity followed moments after crossing under the checkered flag when a tire blew and Lazier crashed at unabated speed. Uninjured, he climbed from the battered car, but whatever earnings third place offered would be needed to purchase and prepare SSM’s third chassis of 2001. Lazier would take it to 12th in Kentucky.

Pole at Richmond.

And we soon discovered Lazier’s pole and podium caught the attention of the IRL’s biggest team and wealthiest team owner, John Menard, who sacked his 1999 IRL champion Greg Ray. For the next race at Gateway, SSM welcomed another CART veteran in Alex Barron to drive the latest No. 99 entry. He’d get tangled in an early pit lane crash and, somewhat famously within the team, is remembered for climbing from the car, making a beeline for the transporter, swiftly changing into street clothes, and leaving without saying goodbye. He was gone so fast, the TV crew searched in vain for the Californian to get his side of the story.

Hearn was back for the penultimate race at Chicagoland where he delivered again with a sixth-place finish. The race weekend was also memorable for Hamilton’s return to the paddock, some 84 days after the Texas crash.

Seeing Hamilton in a wheelchair, with portions of his feet exposed through the casts, was unsettling. We were delighted to see him, but there was no hiding the powerful before and after imagery in front of us.

On the one hand, it might have been best to keep his lower extremities fully covered, but would that have created more questions than answers about how much was left beneath the blanket? Or was the choice to leave the covers pulled back just enough so people could see the damage—but also that he was fully intact—the better message to send?

Hamilton: For a lot of athletes, our DNA is just different. Even athletes from skydiving or a rock climber that’s been through tragedy, they want to do it again. Racing drivers we’ve seen that already. There’s so many of us that this is all we know, it’s what we love. I grew up, a kid from Idaho, and I wanted to drive a race car. It was very tough. There’s not much of that happening in Idaho. It was against the odds. And before the crash, I’m living my dream. My dream was to be in one Indy 500. Well, I was so fortunate to take it way beyond that and run a lot of IndyCar seasons and a lot of Indy 500s.

Different DNA: Eddie Cheever Jr., Billy Boat, Davey Hamilton. LAT Photographic/F. Peirce Williams

And so I figured that if they’re going to do all that work and spend all that time working to fix me, the least I could do is put every ounce of effort I have into it to make it successful. And so just being at the racetrack, being around cars, keeping up with you guys, it just helped me be positive that it was gonna happen again.

One byproduct of being sidelined came with Hamilton and Schmidt spending more time together and building a deeper relationship. Schmidt’s ongoing ordeal with paralysis also produced a harsh wakeup call for his wounded driver.

Hamilton: Before we were both injured, we were both healthy guys racing in the IRL. I was living out in Las Vegas, like Sam, our families went to the same church, and we got to be friends. And then when he had his accident, we were on the same flight from Vegas to Orlando, and were supposed to be on the same flight back, actually. It starts right there when Sam had his unfortunate accident, and everything he went through, and then to come back with a team of his own.

Then we put a good deal together for me to drive for him. I was with him a lot, helping him and learning his challenges, which he has plenty of, as we all know, as far as everyday life. And then when I got hurt driving for him, he was a huge support system to me, his family was there.

I remember him coming to the hospital, and I’m whining and moaning, saying ‘Why me,’ and Sam looks at me and goes, ‘Well, you want to trade?’ And I’m thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, how can I be complaining, and this poor guy is quadriplegic? And he has such a positive attitude?’

That right there changed my whole outlook, him challenging me on whatever I was complaining about. He’s right. It could be way worse. I’ve just got to deal with it and I’ve got to overcome it. That was the reality check I needed.

SSM closed its tumultuous rookie season at the delayed finale in Texas, which was moved from running on its original date just days after the attacks of September 11, to early October. Rapid South Carolinian Anthony Lazzaro, our fifth driver across 13 races, was one of many who failed to finish that race. Knowing how our last trip to Texas ended, there wasn’t much enthusiasm during our return—especially after finding no changes had been made to protect drivers from the exposed poles that savaged Hamilton.

Hamilton: For every single person, I’m going to voice my opinion for safety. There’s issues today that I still am concerned about, but those poles and fencing, nobody that I’ve ever showed that to, whether they’re professional or amateur, can say that’s right. And I’m still surprised and shocked that some tracks are still that way. Why? Tell me why it’s safer that way. I’m just asking the question. Show me why you do that, to make it safer. And I still today, 20 years later, have not got that answer of why they’re built that way. And it’s very frustrating to know that because it can happen again.

Trammel: Go back to Davey’s crash. Anytime you penetrate a fence, whether it’s Pocono, Indianapolis, Texas, the outcome is going to be bad. And that that’s the real backstory. What’s changed in the last 20 years to make it safer? And my answer is not a damn thing as far as the facilities go. Yeah, the SAFER barrier, that’s a whole separate deal. But we’re talking about retaining the car in the ballpark without damaging the driver.

The first No. 99. LAT Photographic/F. Peirce Williams

Another driver in Schmidt’s team, Canada’s Robert Wickens, met a similar fate to Hamilton’s in 2018 when his Dallara DW12 made contact and got airborne. He struck a pole at the Pocono Superspeedway before becoming entangled in the fence and crashing back to earth.

Trammel: Fast forward to Pocono, and that fence was in poor shape to start with. Nobody argues, without question, that it was the impact with the pole that did Wickens’ back in. I’ve never seen anybody go through a fence that got out of it with nothing. You don’t walk away Scot free if you punch a hole in the fence at those speeds.

The mention of Wickens, who continues to rehabilitate from a spinal cord injury that’s paused his racing career, takes the conversation on a different course.

Starting with Schmidt’s Texas crash in 1999 and the fateful January 4, 2000, crash in Florida that brought the paralysis he continues to battle, his drivers have also suffered an unimaginable string of misfortunes since Hamilton’s incident in 2001.

Schmidt: I guess it’s a little bit symbolic of the whole situation. Had I known then what I know now between 2011 to 2018, even Mikhail Aleshin’s crash at California Speedway in ‘14, I don’t know if I’d be doing this now. It’s a lot. We had a Indy Lights driver (Tom Wood) who had severe back injuries in Kentucky. And Hinch (James Hinchcliffe) at Indy 2015. In the 20-year time period we’re talking about since we started the team, we’ve been hit hard by it. And we look in the mirror and are like, ‘What the hell?’

We’re preparing the cars to the best of our ability, we’re doing everything we possibly can and ultimately, you wonder, ‘What can we do differently? What can we possibly do? It’s frustrating, extremely frustrating.

Damage from Aleshin’s entanglement in California Speedway’s fencing.

Russia’s Aleshin nearly died in the superspeedway crash that tried to tear a valve away from his heart. Canada’s Hinchcliffe nearly died due to blood loss when a suspension failure in practice for the Indy 500 speared a long piece of metal tubing through his upper leg and groin area. Wickens was paralyzed from the waist down and has worked tirelessly to regain as much mobility as possible.

Saddest of all was two-time Indy 500 winner Dan Wheldon, driving for Schmidt at the 2011 IndyCar season finale at Las Vegas Motor Speedway—owned by the same parent company of TMS—where a giant crash and a helmet strike against an exposed pole killed the Briton.

Hamilton, Wood, Wheldon, Aleshin, Hinchcliffe, and Wickens. It’s a lot to bear for any IndyCar team over 20 years.

Schmidt: You look at all the things that are taken and given, like the pole at Indy with Hinch in ’16, but then Robby’s crash in ’18. And it’s a constant back and forth on good and bad things happening. I think the closest I ever came to just hanging it up was 2011 with Dan. With Davey, we were so fresh, we just got started. And it’s like, well, we can’t quit now, right? And I spent some time talking to Davey, too, and he encouraged us to carry on. It wasn’t anything he’d done. Wrong place, wrong time. But it happened. So, you carry on with the team, but at the end of 2011, it was probably the worst.

It took six years of pushing through more surgeries and physical therapy for Hamilton to make a jubilant return to racing at the 2007 Indianapolis 500. He’d return each month of May through the 2011 event and add three other IndyCar starts before retiring on his own terms.

Once the early days of restoring blood flow had a positive ending, one of Hamilton’s surgeons never doubted whether he’d get back to racing.

Trammel: You take things on baby steps. The overriding thought is, will it survive, the toes or whatever piece that you put back in? And so your overwhelming thought for the immediate term, is will this make it? One of the earliest for me was Mears.

I came home from the first real Holy Mary surgery on his feet, and I didn’t think the left one was gonna make it. I sat at the kitchen table, looked out on the woods behind my house and there wasn’t anything else I could do. And I waited until the sun came up, got in the car, and went back to the hospital. And his toes were still pink, and it was like, OK, one day at a time. We made it another day, and then we made it another, and you have some setbacks, but we won the war.

Those guys like Hamilton, and that courage that they have, every one of them, they’re just a unique breed. There hasn’t been anybody that says, ‘I can’t do this, just cut this thing off.’ I’ve never ever heard a driver say that. The first question is always, ‘Will I be able to drive again?’ Nobody ever asks me first, ‘Can I walk?’ It’s ‘Can I drive?’ Just a unique breed.

Davey Hamilton at the 2011 Texas race. LAT Photographic/Mike Levitt

Of the 11 Indy 500s on his resume, five came after his Texas 2001 crash, and with his racing days in the rearview mirror, Hamilton’s next chapter was a heartwarming venture. Starting in 2012, Sam Schmidt Motorsports became Schmidt-Hamilton Motorsports when the friends reunited as IndyCar team co-owners. Ric Peterson would join the ownership group in 2013, and after the conclusion of the 2014 season, Hamilton stepped aside.

With his sponsor Hewlett-Packard serving as primary sponsor of Simon Pagenaud’s car over the three-year span, Hamilton was part of the team’s greatest period of success as the Frenchman placed fifth, third, and fifth in the championship prior to signing with Team Penske for 2015.

Hamilton: When we had the opportunity to do the three years together in ownership with Simon as our driver. That was a dream come true for me to become a team owner like Sam did.

Following IndyCar team ownership, Hamilton kept busy with a short oval racing series, supporting his son’s racing career, driving IndyCar’s two-seater promotional vehicle at events, and he continues to work as part of the IndyCar Radio Network. And it’s the two-seater where he had some fun at the expense of the good doctor.

Trammel: He’s never lost his sense of humor. We were at Colorado for an oval race there, it’s the Thursday, not much is going on, and he’s like, ‘Come on, get in.’ I said, ‘Hell yeah, here we go.’ So we’re going out and chugging along. A little faster, a little faster, a little faster. We’re getting closer and closer to the wall. I lean over the top of the seat and yell up underneath his helmet, ‘If you hit that wall, who’s going to take care of us?’ He said something like, ‘Just keep your hands in the car!’ Because we were we were close to wall, I thought we were going to white-wall the tires. He obviously didn’t think so, but wow, it was a good, good laugh for him to try and scare me.

Hamilton celebrates the team’s first win at Detroit 2013 with Schmidt, Ric Peterson, and Simon Pagenaud.

Schmidt’s the only person from that original 2001 team who is involved with its modern incarnation in 2021. Many of the newer employees of AMSP are likely unaware that the emergency response protocols they drill with today were spawned from Hamilton’s crash in SSM’s infancy.

Schmidt: It was a legacy of Davey’s accident where, over time, you develop a pretty substantial catastrophe plan for a lot of different things. It’s just like having spare parts for things hoping you’ll never need them. Same thing. It’s really comprehensive. There’s a hard copy, there’s soft copy, it’s accessible by all the key players in the team. We have people that are designed specifically to go to the infield care centers, specifically to talk to the media, specifically to look after the loved ones of the person that got injured, transportation people, notification people; it’s all pretty well laid out. And unfortunately, it has been developed with practice.

And there’s one more legacy item from June 9, 2001, to reconcile.

Hamilton’s tattered car from Texas stayed in the top of SSM’s transporter for a decent period of time. It was eventually unstrapped and taken inside the LP shop located amid farmland in Brownsburg, Indiana, but like many things about that exhausting season, I’d forgotten its final resting place.

Patterson: It ended up in an old chicken coop – where race car parts went to die.

Thinking that was the end of the story, a fascinating plot twist emerged from the man at the center of this tale.

Hamilton: I’ve got it!

Wait, what?

Hamilton: How I ended up with it, ironically, is Dallara wanted it to do some R&D. Larry gave it to Dallara so they could see what they could do better. Before Dallara built a building of their own in Speedway, they were over with the two-seater guys on Gasoline Alley. I want to say it was maybe six years after the crash, my friend out of Idaho who I went to school with, her company was hired to hang a car up at that Indy 500 restaurant at the airport in Indy.

So she reaches out to me, says she knows I race Indy cars, asked if I knew of any old cars she might get her hands on for this installation project she’s been hired to do on the wall, so I reached out to Jeff Sinden at the two-seater place and he said to come by and look around upstairs and see if any of the old stuff they had could work. I get over there, go upstairs, and I see a tarp. I pull the tarp off, and there’s that tub of mine!

That was a first for me, obviously, seeing what was left of it. I had no clue that that thing still existed. So I went to [Dallara USA boss] Stefano DePonti and said, ‘Do you guys still need that?’ He said they didn’t need it anymore, so I said, ‘I’ll take it.’ I don’t know what I’ll ever do with it, but I do still have it.

And that closes the chapter on an amazing arc for Hamilton, Schmidt, and all who’ve been connected to the various turns through trauma and resilient survival since that day in Texas.

Hamilton: I didn’t even realize it’s been 20 years. When you go through something like that, time moved so slow going through the healing process. It seemed like a day took a week. Dr. Scheid, we’re still buddies. I just talked to him the other day; he needs some stuff done on a pickup truck he got for his wife. We stay in touch. And Denise Titus, the IRL nurse; when you say angels, that is an understatement, honestly.

And not just for me, but my entire family and friends and people that were involved. I’d do anything for them for the rest of my life. And Doc Trammel I see around all the time, and Sam, and a lot of the gang from back then are still around, still doing their thing. Obviously, I owe them so much. And now, all of sudden, I’m looking back as 20 years have gone by. Wow.

The amazing Davey Hamilton. IMS Photo